This post discusses the anchoring bias. It’s a pretty straightforward bias to understand, but it’s also very surprising how we’re impacted by sometimes even the most random of anchor points when it comes to making decisions. We chat to Louise Bedford who shares some anchoring effect examples with us and gives some valuable tips on how to both identify and then minimise the impact of anchors in your trading decisions. Don’t be the anchored trader.

In fact, let’s start with a quote from Louise:

Anchors – it’s such a good word, isn’t it? Because it ties us down to the ground in some way.

You can catch this episode on our YouTube channel or via your favourite podcast platform. Just click on the links and opens in a new tab. Or you’d rather read about the anchored trader… just keep scrolling.

The first thing we need to do is define what an anchor point actually is. It’s quite simple.

An anchor point in decision making is what we use to start the thinking process, specifically when we need to guess something. Or what’s that great term – ‘guess-timate’.

If we had to guess when Albert Einstein was born or the height of the Eiffel tower, we’d use an anchor.

There have been countless experiments of the anchoring effect. Probably the most well-known being Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman’s wheel of fortune experiment where they showed how a completely irrelevant number affects decision making.

In the interest of science, we decided to hit the streets of Cape Town and see if we could perform a little anchoring experiment. We asked people to tell us the last 2 digits of their mobile phone number and then tell us how much they were willing to pay for a tin of tuna. Random, I know – but that’s the point of the whole experiment, to be random!

The results showed that we are clearly influenced unconsciously by anchor points – even random ones. Those with higher digits for their mobile numbers gave higher prices for the tin of tuna. Scroll to timestamp 5:27 in the YouTube video if you want to see the full results of the experiment.

It’s a little bit frightening how easily we can be influenced by something so random and so simple.

In our previous post we spoke about the framing effect.

As a reminder…

Framing is a bias that’s not about the specific information that you’re presented with, but rather how that information is presented to you. In other words, it’s not what you say, but how you say it. Essentially, the framing of information changes your perception of the actual information.

This is very apparent in the investing world where we make different decisions when we are faced with possible losses rather than possible gains. That’s the whole topic of risk-aversion and loss-aversion, which you can read about here.

And this is why we have what’s known as the anchored investor: an investor who is anchored to the original purchase price. Or the anchored trader, something we chat to Louise about…

We chatted to Louise Bedford, one of Australia’s best-selling authors, a trading mentor, and host of Talking Trading podcast. We asked her to share some examples of common anchors she’s seen influencing trading decisions?

Let’s have a look at three specific anchors.

The first one would be stock anchoring.

Stock anchoring is when people think the price they get in at is the only truth in the entire world and everything is anchored to that price. So, they think if it goes up ‘Oh, how much money have I made because I got in at this price and I’m going to get out at this price.” It actually inspires us to have much more fear and greed than you would expect. We need to [rather] look at each stock individually. That emotional attachment to a stock does none of us any good as traders.

The other type of anchoring is identity anchoring.

I am this type of person. I am this type of person because I never make a loss in the markets. I am a good trader. I always stick to my trading plan. We anchor ourselves to our identity principles and we have trouble moving away. If we do have to move away that inspires cognitive dissonance which is that uncomfortable feeling when there’s a mismatch between your actions and values. So, be careful about the identity cues that you’re allowing into your own mind.

The other type of anchoring is future anchoring.

This is where we imagine ourselves in the future and we work out how do we get from where we are now to where we want to be. That future anchoring can be quite insidious if we are used to having a job, but then all of a sudden, we have a disability or maybe there’s an interruption to our work life. We think of ourselves as a type of person that’s working to the age of 65 and retiring, because that’s our future anchor. But we’ve been thrown that curveball and it can actually sweep us off our feet. Be careful about the futures that you anchor to and make sure that they are broad enough to encourage a variety of different circumstances. Otherwise, you might just get hooked into a future that you are not wanting for yourself currently.

In short, it’s good to have a 5-year plan and a 10-year plan, but you’ve got to be careful of anchoring yourself too much to that plan.

We asked Louise if there are any tell-tale signs that we can pick up to warn us that we’re being held down by an anchor:

One of them is definitely reluctance to sell a stock or even reluctance to buy a stock. This reluctance in the face of all the evidence that you’ve got in your trading plan. All the evidence from your charts is telling you one thing but you are feeling another way. That internal friction is the thing that wakes us up at 3am in the morning!

The other is information aversion. [This is where] when we are doing well in the markets, we check our portfolios 500 times during the day because it just gives us that dopamine kick and we’re so happy with ourselves. But when things aren’t going as well, we avoid looking at our portfolio. That can be to our detriment. That is one to look out for in terms of your own behaviour. How often are you checking your stocks and is that something that you are comfortable with?

The other would be money scripts. These are the concepts that are passed down to us, often multiple generations are responsible for this. It’s the things that we heard at the top of the stairs as a child. What are the money scripts that we have from our parents and from our grandparents that tell us whether money is good or bad? How should we respond to money? And what is our physiological reaction? If you are ever sitting in front of a computer screen and you can feel yourself starting to sweat, you can feel your heart rate increase, you can feel your breathing becomes shallower… All of those are physiological reactions that could be related to your money scripts and how you’re feeling that represents itself physically.

Very useful tell-tale signs for us to look out for.

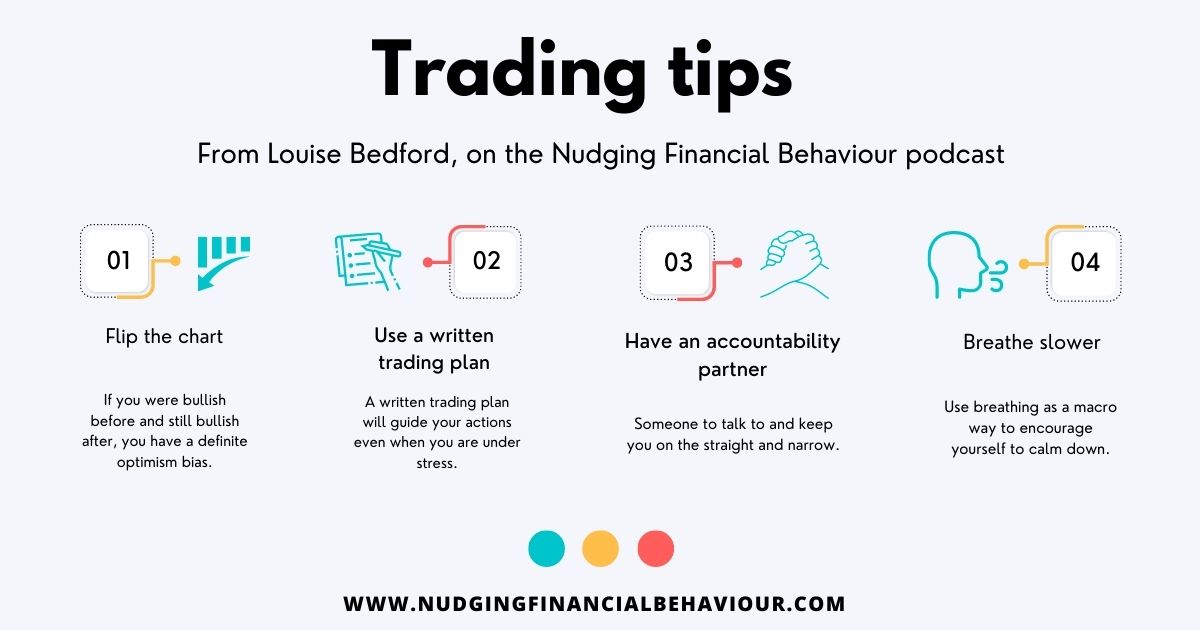

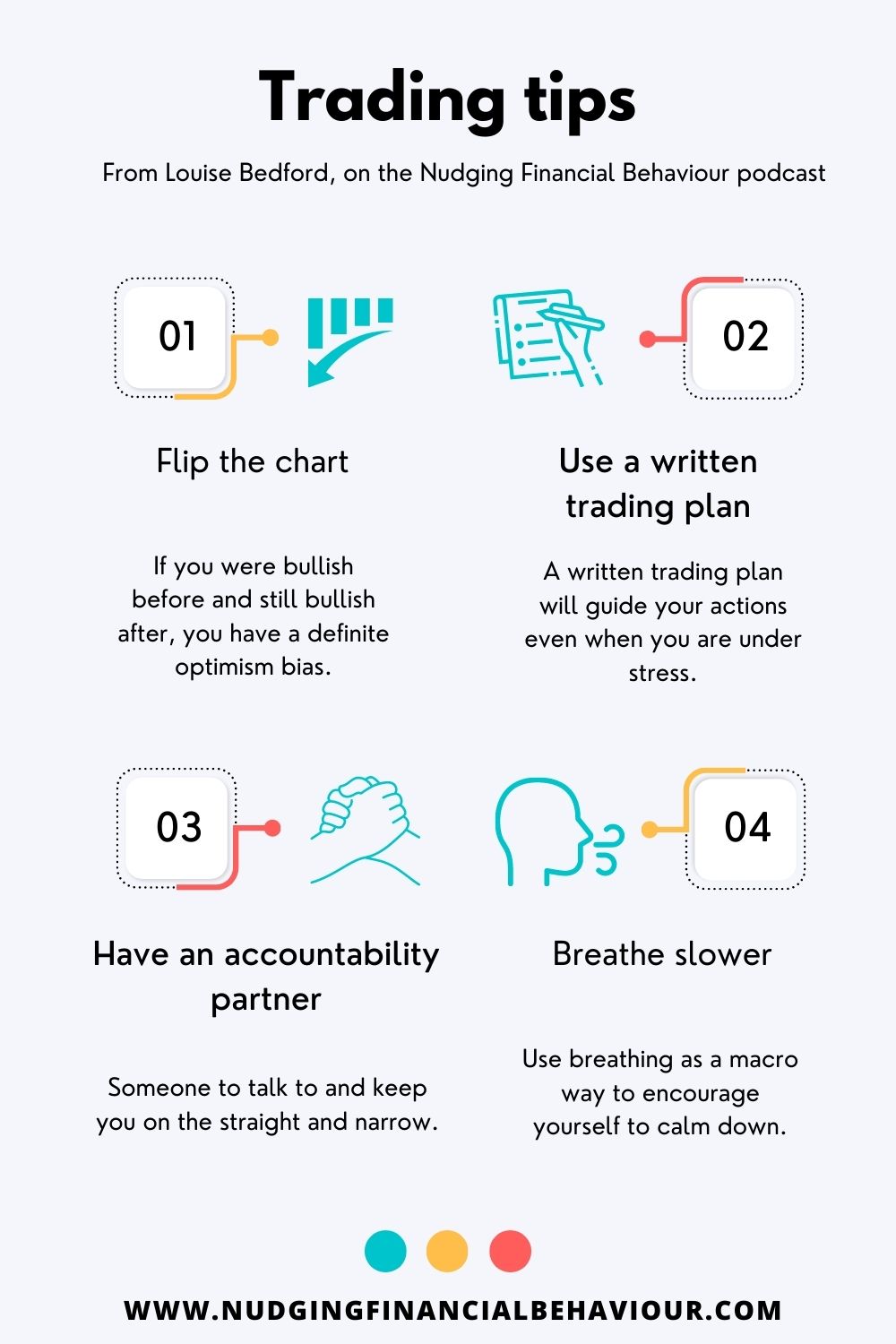

Finally, Louise gave some tips on how we can then go about overcoming those anchors with our trades?

The first one I think we should all get into the habit of doing is, if we’ve got a charting package that allows us to flip the chart upside down, if when it was around the right way you were bullish and then when you flip it you are still bullish, you have a definite problem. That is absolute evidence that you have an optimism bias. You’re only seeing the best and that bites us as traders.

The other thing we can do is use a written trading plan. This is important because a written trading plan will help guide your actions even when you are under stress.

Another aspect you can look at is using an accountability partner. Have you got a trading partner that you can talk with that can help keep you on the straight and narrow?

And perhaps my other thing to advise is to ‘breath slower’. Often in the markets, when we have that rush, that feeling that everything is coming up into our throat because everything is contracting, we need to use our breathing as a macro way to encourage us to calm down.

So, I do think those areas where we are turning the chart upside down, using a trading plan, using an accountability partner, and using simple commands to breathe slower, can all help us overcome our anchors.

Such valuable insight. So much to think about there. Perhaps we should all be printing out a sign to remind ourselves to breathe slower to hang above our desks?

So, now that you know about anchors and how they can be totally arbitrary or they can be deeply ingrained in us from childhood, what do you do next? What strategy can you create to support your capital accounts?

As I’ve said again and again, being aware of the bias is the first step in interrogating whether it’s helpful or a hinderance.

We're constantly being anchored by reference points and we need to be able to spot them. Share on XRight, it’s time to say anchors aweigh on this post. Our next post is going to recap everything we’ve spoken about in this season and… we have a couple of bonus questions and answers to share with you from each of our interview guests this season. You don’t think we let them off that easily, do you?

Let us know in the comments below.

I am passionate about helping people understand their behaviour with money and gently nudging them to spend less and save more. I have several academic journal publications on investor behaviour, financial literacy and personal finance, and perfectly understand the biases that influence how we manage our money. This blog is where I break down those ideas and share my thinking. I’ll try to cover relevant topics that my readers bring to my attention. Please read, share, and comment. That’s how we spread knowledge and help both ourselves and others to become in control of our financial situations.

Dr Gizelle Willows

PhD and NRF-rating in Behavioural Finance

Receive gentle nudges from us:

[user_registration_form id=”8641″]

“Essentially, all models are wrong, but some are useful.” – George E.P. Box