Can you believe we’re already halfway through Season 2 of the podcast? In this post, we’re unpacking a bias that has a lot to do with how readily available information is – availability bias. We’ll also look at survivorship bias, which is quite closely linked to availability and can have a big impact on investment decisions. My guest in this episode is Hersh Shefrin – a pioneer and legend in the field of behavioural finance. If you know the name – you’ll know that there’s no way we could do this interview without talking about two treacherous emotions – fear and hope (yes, we’re rebranding greed to hope)!

In our conversation with Hersh, we gain insights into the intricacies of availability bias and its impact on investment decisions. He highlights the danger of investors fixating on readily available information, overlooking nuanced risk factors that could lead to significant losses.

Don’t forget to subscribe to our channel so you know when new episodes come out. This latest episode is also available on any of your favourite podcast streaming apps.

We make decisions based on the information we have at our disposal – and this is where availability bias comes in. It’s a cognitive shortcut which distorts our decision-making by giving undue weight to information that is easily accessible.

A great example of this was the movie, Jaws.

People around the world suddenly became terrified of swimming anywhere – not just in the ocean. The film was made in 1975, and people who watch it today still get scared of shark attacks thanks to the movie.

And this is ridiculous, because the likelihood of being attacked by a shark while swimming in the ocean is 1 in 4.3 million according to the International Wildlife Museum.

But because the shark attack scene was so graphic in the movie, we distinctly remember it, and thus we heighten the probability of it happening to us next time we have a day at the beach.

In my own life, I saw this bias play out just last year. For my birthday, my friends got together and bought me tickets to go paragliding here in Cape Town. Something I’ve always wanted to do.

I got two tickets. (It’s obviously more fun jumping off a mountain with someone than by yourself.)

But right around that time, there was a freak accident in Cape Town, and someone got killed paragliding. Yes, it was very sad, but that didn’t mean I was more likely to have an accident when I went.

Rationality aside, suddenly, everyone who was so excited about me paragliding and people who were my potential jumping partners, were no longer interested. They were suddenly really worried that something similar would happen to them.

Fortunately, I do have one friend who is crazily adventurous like me, so, we went paragliding together. I’ve included a video of our flight in the episode. Feel free to watch me jump off a mountain!

I’m hoping you can see how this bias plays out. Recent events can disproportionately influence our perceptions of risk. The vividness of certain events, such as shark attacks in the movie Jaws or a paragliding accident, can inflate their perceived likelihood, despite their actual rarity. But this is a little nonsensical. Things don’t have a heightened chance of happening just because they happened recently or because we can visualise them better thanks to a movie or the news.

Our minds gravitate towards readily available information, often overlooking more statistically significant factors. Share on XSocial media coverage plays a big role with availability bias. An event that is possibly very rare – like a gas explosion in the streets of Johannesburg – might become more visible to us because there is large coverage of it online. Feel free to check out another post of ours where we cover this in more detail.

And recall our interview with Rachel Alberts in Season 1 where she spoke about the social media echo chamber effect. This is very relevant when it comes to availability bias.

But it’s not just social media. It’s the news in general.

There has never been so much news about the world available to us as there is right now. And it’s coming from everywhere – on our TVs, our computers, our phones, even notifications on our smartwatches.

The mind is not a vessel to be filled, but a fire to be kindled.

Author and entrepreneur, Rolf Dobelli, has given some amazing talks on living without the news. His view is that we don’t need the news, the constant barrage of headlines about stories that don’t impact our lives in any way.

Now, he’s not saying that we shouldn’t be informed about the world around us. But rather, we should explore significant events, people and places, and gain an in-depth knowledge of the parts that truly impact us. Here’s a link to a TedTalk he gave on the subject matter.

Our constant scrolling through news headlines on social media, news apps and websites is not keeping us informed. It’s feeding into a global anxiety and feeding into our biases – especially availability bias.

We also have to look out for the fact that many professionals fall victim to this bias in the workplace. And then there’s also survivorship bias that we need to be careful of (more on that later).

Time to get some insight from Hersh Shefrin, professor of finance at the Santa Clara University in California. He is a prolific author, publishing numerous books on behavioural finance. And in 2003, the American Economic Review listed him as one of the top 15 economic theorists to have influenced empirical work. We asked him to share some of his thoughts on availability bias and how it affects our investing decisions.

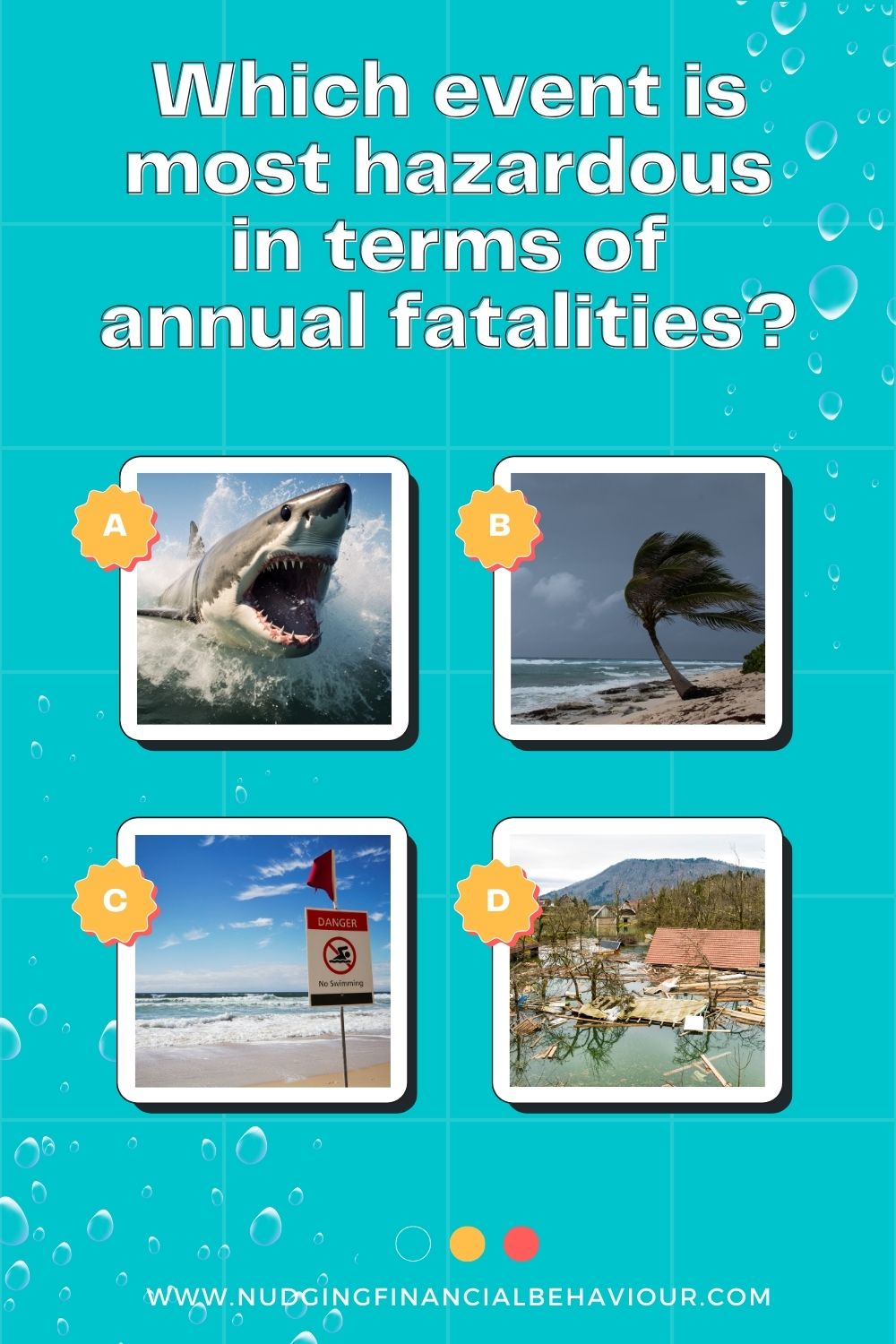

What I ask my students to do is to consider four hazards related to water and I ask them, what do you think is the most hazardous in terms of annual fatalities? So here are the four: shark attacks, hurricanes, rip currents, and floods. So, if you think about those four, you can sort of consider in your own experience, wherever you are in the world, which of those is the most dangerous?

In the US, the answer turns out to be rip currents. And that is typically a huge surprise to most of my students or most of the audiences to whom I pose this question.

Rip currents are simply people walking out into the ocean and being dragged out and drowning. And there are more rip current deaths per year than deaths from any of the other three. And the question is why. And it’s largely because the media reports on dramatic events like shark attacks and floods and hurricanes. But rip currents simply are individual events that very rarely make the headlines.

And so… information about rip currents is not readily available. The way information about shark attacks, hurricanes and floods is readily available. And that’s why we have a bias called availability bias. Availability bias means putting too much weight on data sources that are readily available, especially if the source of the data is memory.

The greatest enemy of knowledge is not ignorance, it is the illusion of knowledge.

As we can see from Hersh’s example, hurricanes and floods are what people know about. And movies, like Jaws, remind us about shark attacks. But these events are not as prevalent as we might think.

Availability bias also extends beyond individual decisions, permeating corporate strategies and societal perceptions. Take, for instance, the design flaw at Fukushima Daiichi, where the recent memory of earthquakes overshadowed the historical data on tsunamis, leading to catastrophic consequences.

Here is a real-world water hazard example… It relates to Fukushima Daiichi, the nuclear reactor that experienced a meltdown in Japan about a decade ago. And why did it experience a meltdown? It experienced a meltdown because of a combination of an earthquake followed by a tsunami that struck the reactor itself.

Why would availability bias figure in to this particular event? It figures in because of the way the Japanese built Fukushima Daiichi. They built it to withstand a major earthquake, but not a major tsunami. And why would they do that? It’s because the Japanese experience a lot of earthquakes, but far fewer tsunamis (even though tsunami is a Japanese word). Tsunamis are just not part of the Japanese consciousness, at least they hadn’t before Fukushima Daiichi. Than earthquakes are.

So, availability bias was a strong driver of the design of Fukushima Daiichi that led them to be vulnerable to the impact of a major tsunami.

When you try to assess the risks, you plan for a one in 10 000-year event. That’s what they should have done with tsunami data. Thought about what happens over a 10 000-year period in respect to the histogram of major tsunamis. But they didn’t do that. They chose just one data point. A recent tsunami off the coast of South America that was relatively minor compared to what they actually experienced. So that event, because it was relatively recent when they were doing the design, it was a readily available event, and so they succumbed to availability bias.

In the domain of investments, availability bias can blind investors to hidden risks, as observed in the case of BP’s Deepwater Horizon disaster. Despite warning signs, investors, swayed by the company’s public image, underestimated the potential hazards, highlighting the perils of overlooking less salient information.

I hope many of you will recall the catastrophic events around the explosion of Deepwater Horizon in the Gulf of Mexico. I will tell you that two years before that explosion, I wrote that I thought that most investors had the wrong perspective on BP stock and BP as a company, that most investors thought that BP was an environmentally friendly company because it invested in alternative energy. And it was very good at PR. But if you actually looked at what BP did, if you looked below the surface, if you looked below the level at which data was readily available, you’d see that it was an environmentally hostile company.

It was winning all kinds of awards for being socially responsible before Deepwater Horizon. But the real story was different. …in the end availability bias prevailed both within the company, in BP, but also in the investment community in terms of investors who invested in BP.

Such a powerful bias and some really impactful examples that Hersh shares. Something that’s closely linked to availability bias is survivorship bias, which adds a whole other dimension to things…

The important thing is to not stop questioning. Curiosity has its own reason for existence.

Survivorship bias compounds the distortions wrought by availability bias, as it emphasizes observed successes while overlooking failures. We celebrate triumphs but neglect the countless failures that precede them. This bias skews our perceptions of risk and success, fueling overconfidence and misguided decision-making.

Consider the tech industry’s darling, Apple, celebrated for its meteoric rise. Yet, overlooked are the myriad failed ventures in the same domain, such as Palm, obscured by the shadow of Apple’s success.

Think about Apple as a company, the most valuable company in the world. It invented the iPhone, and it has certainly survived and thrived. But living in Silicon Valley and having lived in Silicon Valley through the 1990s, through the dot-com bubble and the period thereafter, you also see other companies that were working on developing smartphones besides Apple. Palm, for example, was a company that was really famous around 2000 and yet it didn’t survive. So, we think about Apple in terms of its success. But we encounter availability bias when it comes to the firms that didn’t survive. And so, then you get availability bias driving survivorship bias. There’s only one winner. We remember the winners.

Similarly, financial analysts’ rosy projections for tech giants may reflect an overestimation of future prospects, rooted in survivorship bias.

This is an issue from a research perspective when you’re trying to think about how to fundamentally value a company. So, for example, in my research, I’ve looked at a set of six technology stocks, Microsoft and then an acronym called FAANG, Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Netflix, and Google, now called Alphabet. When you look at these companies, they are major companies, but in the way that their value is assessed by financial analysts.

Financial analysts tend to be excessively optimistic about the value, the valuations they place on these companies. And it happens because they commit a bias called growth opportunities bias that stems from availability bias. And growth opportunity bias is the assumption that a successful company can earn more than its cost of capital indefinitely. It will always be a winner into the long term, it’s not just a short-term phenomenon. And we teach in textbooks, we teach our students to be really careful to assume that in the long term, you shouldn’t expect companies to earn more than their cost of capital, unless there’s a good reason to do that, like patent protection or government protection.

It’s important that financial analysts be careful about this. And honestly, for the most part, they’re not. So, this is kind of an issue that comes up that links the two issues… availability bias and survivorship bias.

I have a personally signed copy of one of Hersh’s books: Beyond Greed and Fear, so I needed to ask him about it… [sorry to brag… I tell the full story of how I met Hersh in the episode.]

I started out in the behavioural area focusing on the fact that when people make decisions, they do it by combining mental inputs based on both how they feel and what they think. And how they feel is critical. So, balance is important because most of us really need to have these two elements in our minds both helping us to assess situations and figure out what makes sense in terms of decisions.

Too much fear or too much, I prefer the word hope to greed… I should say that greed is really, it’s one of the deadly, fatal sins. Hope isn’t a sin. But it’s really hope people have in mind when they use the term greed. Hope is a feeling of optimism about favourable outcomes occurring, and it’s the need to feel successful as well when you set yourself goals. If we have excessive fear or excessive hope that take us out of balance relative to being grounded in reality, then we might wind up erring in terms of the investment decisions we make, particularly for retail investors, individual investors. If too much fear, then we might proceed with too much caution. We know the expression fight, flight, or freeze. Fear tends to make us freeze when we need to take action, and it might lead us to engage in excessive flight when that could be to our detriment.

On the other hand, excessive hope can lead us to engage in excessive risk taking where we are imprudent in the way that we take risks, going after too much upside and then suffering the consequences because the downside is what actually occurs.

So, the lesson that I offer in Beyond Greed and Fear is it’s really important to have an internal dialogue, a dialogue inside our minds between asking ourselves about how we feel explicitly, what we’re thinking, and then trying to get this balance so that the two aspects of our brain, the two activities, inform each other. And that should sort of keep us in check.

At the very end of Beyond Greed and Fear, I just provide a short set of suggestions for retail investors. And the suggestions go something like this. The difference between behavioural finance and standard traditional finance is that those of us in behavioural finance believe that markets are not always efficient, that there are opportunities for positive alpha, that you can, in theory, sometimes beat the market because of mispricing. But if you choose to try to earn positive alpha, please remember you expose yourself to an additional source of risk besides financial risk. You expose yourself to sentiment risk. The risk of other investors making mistakes that cause your best laid investment plans to go awry.

You take on excessive risk when you go for alpha. And in addition, your own biases might be too powerful, and they negate your opportunity to actually capture the alpha that’s there. So, it’s really complicated, much more nuanced and subtle than our intuition tends to suggest to us. And these are things to keep in mind when we are setting out to put in place an investment strategy.

Hersh emphasises the importance of balance in decision-making, cautioning against excessive fear or hope (a more apt term than greed). Financial advisors can also play a crucial role in guiding clients through this balance, fostering open discussions and integrating behavioural insights into investment strategies.

I think that financial advisors need to understand that their roles are not just about advising on portfolios or constructing portfolios or doing small questionnaires to elicit risk tolerance. But they really need to have a behavioural skill set that goes along with the financial skill set. And that behavioural skill set includes the ability to structure conversations with clients about the internal dialogue. They need to get comfortable asking their clients how they feel. They need to get comfortable asking their clients about their emotions. In a sense, they need to have a psychological toolkit that’s similar in nature to what therapists have.

Now, we don’t want our financial analysts to become therapists or to get super deep into issues that really only professionally trained therapists should engage in, but they need to wade into that territory in order to elicit feelings and elicit views on what their clients are thinking and then help them by example. And that often means by using themselves as examples. Explain to their clients how they think about managing the internal dialogue, the internal conversation about feelings and thoughts.

And of course, supplying their clients with perspectives and facts in terms of what to think about. So, it’s about balancing the discussion with clients in the same way that the internal conversation takes place.

We do ask a lot of our financial planners, but this is really an important thing for them to be aware of in their profession and what they do.

It’s so interesting that we use the terms fear and greed… They’re both so negative. Perhaps we should rebrand like Hersh says, and use the term hope rather than greed. That frame gives a different spin on the internal dialogue, and hopefully will help you (and me) to keep balancing things.

Availability bias is absolutely one of the most important biases that you really need to be aware of. It’s so easy to fall prey to it and it can be quite a tricky one to spot. By recognising and mitigating these biases, and having an open dialogue about our fear and greed (hope) we can navigate the complexities of decision-making more adeptly.

Balanced perspectives and informed strategies can provide greater clarity and rationality in our financial endeavours. Share on XI suppose it’s probably wrong that I’m hoping that availability bias will play out encourage you to go subscribe to our channel…

Narrow framing – Narrow framing, the compromise effect, glossing, and the enabling frame. We need frames to make sense of the world. But they cause problems.

The anchored trader – Anchors tie us down and can have serious consequences for investors and traders. Don’t be the anchored trader.

Share your answers in the comments below.

[apsp-follow-button name=’nudgingfinancialbehaviour’ button_label=’Follow on Pinterest’]

I am passionate about helping people understand their behaviour with money and gently nudging them to spend less and save more. I have several academic journal publications on investor behaviour, financial literacy and personal finance, and perfectly understand the biases that influence how we manage our money. This blog is where I break down those ideas and share my thinking. I’ll try to cover relevant topics that my readers bring to my attention. Please read, share, and comment. That’s how we spread knowledge and help both ourselves and others to become in control of our financial situations.

Dr Gizelle Willows

PhD and NRF-rating in Behavioural Finance

Receive gentle nudges from us:

[user_registration_form id=”8641″]

“Essentially, all models are wrong, but some are useful.” – George E.P. Box