This is the 3rd and final instalment in our series on self-control, procrastination, and immediate gratification. Time to understand that we don’t have constant discount rates and thus make different choices over time. Sound complicated? It is a little, but as always, this post is packed with relatable examples to help you understand why we view immediate rewards differently from future rewards. It’s the quintessential hyperbolic vs exponential discounting debate!

Without delayed gratification, there is no power over self.

Imagine that I offered you either $1000 in a year or $1100 in a year and one month? Which would you choose?

Most people select the later larger reward. A sensible choice as an annualised return of 120% over one month is extraordinary.

Now imagine that I offered you either $1000 in cash right now or $1100 in one month’s time? Which would you choose this time?

Would you still choose the later larger amount? Most people don’t. They prefer to take the cash straight away.

In both examples, you merely need to wait an extra month to get that exceptional return. But in the first example, you’ve already waited a year, so one more month doesn’t seem that bad. In the second example though, the reward is much closer, and thus our emotional interest rate is higher. This is the phenomenon called hyperbolic discounting. It refers to our hyperbolic curve which creates this preference reversal.

Present in both the gym and credit examples for self-control was an element of time-inconsistent preferences. In the short run we are impatient (we want to buy now), but in the long run we see ourselves as being patient. Said differently, we have an inflated view of our future selves. We might decide that tomorrow we’re going to eat healthily, and we genuinely see our future (tomorrow) selves doing that. But when tomorrow comes, we end up falling short of that expectation.

In our savings decisions, instead of saving today, we will rather wait for tomorrow to save. But we’re failing to realise that tomorrow we won’t feel like saving either. We struggle with self-control because we procrastinate and put things off. This time preference weighs current consumption more heavily than later consumption.

In standard financial models, investors are assumed to discount at a constant rate (termed the exponential curve or exponential discount function). But that’s not true. Our trade-off between today and tomorrow is not always the same. Thus, modeling these self-control problems require the use of hyperbolic discounting, where the discount rate is steeper in the immediate future.

Consider the example, again, of choosing between $1000 or $1100 a month later. This is akin to the insanely high-interest rates that banks charge on short-term loans, exploiting our need for instant gratification.

For those that understand things better with a graph, I made one for you:

The solid line is exponential discounting. Note the gradual and steady decline over time: The ratio of the x axis to the line vs the y axis to the line is identical at all times. That’s not human behaviour.

The dotted line is hyperbolic discounting. It discounts more than exponential at the start and less than exponential far into the future. This explains why intergenerational equity does not exist.

Intergenerational equity is a concept or idea of fairness or justice between generations. If it existed, we wouldn’t waste water the way we do (because it WILL run out). We wouldn’t put diesel in our cars because it contributes to global warming which future generations will need to deal with. But if we thought that water was going to run out next month… well then, I’m sure you can see how our behaviour would differ. Human behaviour does not make significant sacrifices for events far into the future.

When humans discount hyperbolically they basically disregard future costs. Thus, exponential time discounters have a budget, while hyperbolic discounters have a nice car, a nice house and ugly-looking debt. (For those that are thinking “I have a budget”, we have unique discount rates which range between pure exponential and pure hyperbolic so sure, you might have a budget, but that doesn’t mean you’re not susceptible to this bias.)

We’re also more susceptible to hyperbolic discounting if we’re under the influence of alcohol. Research shows that present bias is highest in drug and alcohol addicts, gamblers, the less cognitively talented, and younger people.

When humans discount hyperbolically they basically disregard future costs. Thus, exponential time discounters have a budget, while hyperbolic discounters have a nice car, a nice house and ugly-looking debt. (For those that are thinking “I have a budget”, we have unique discount rates which range between pure exponential and pure hyperbolic so sure, you might have a budget, but that doesn’t mean you’re not susceptible to this bias.)

We’re also more susceptible to hyperbolic discounting if we’re under the influence of alcohol. Research shows that present bias is highest in drug and alcohol addicts, gamblers, the less cognitively talented, and younger people.

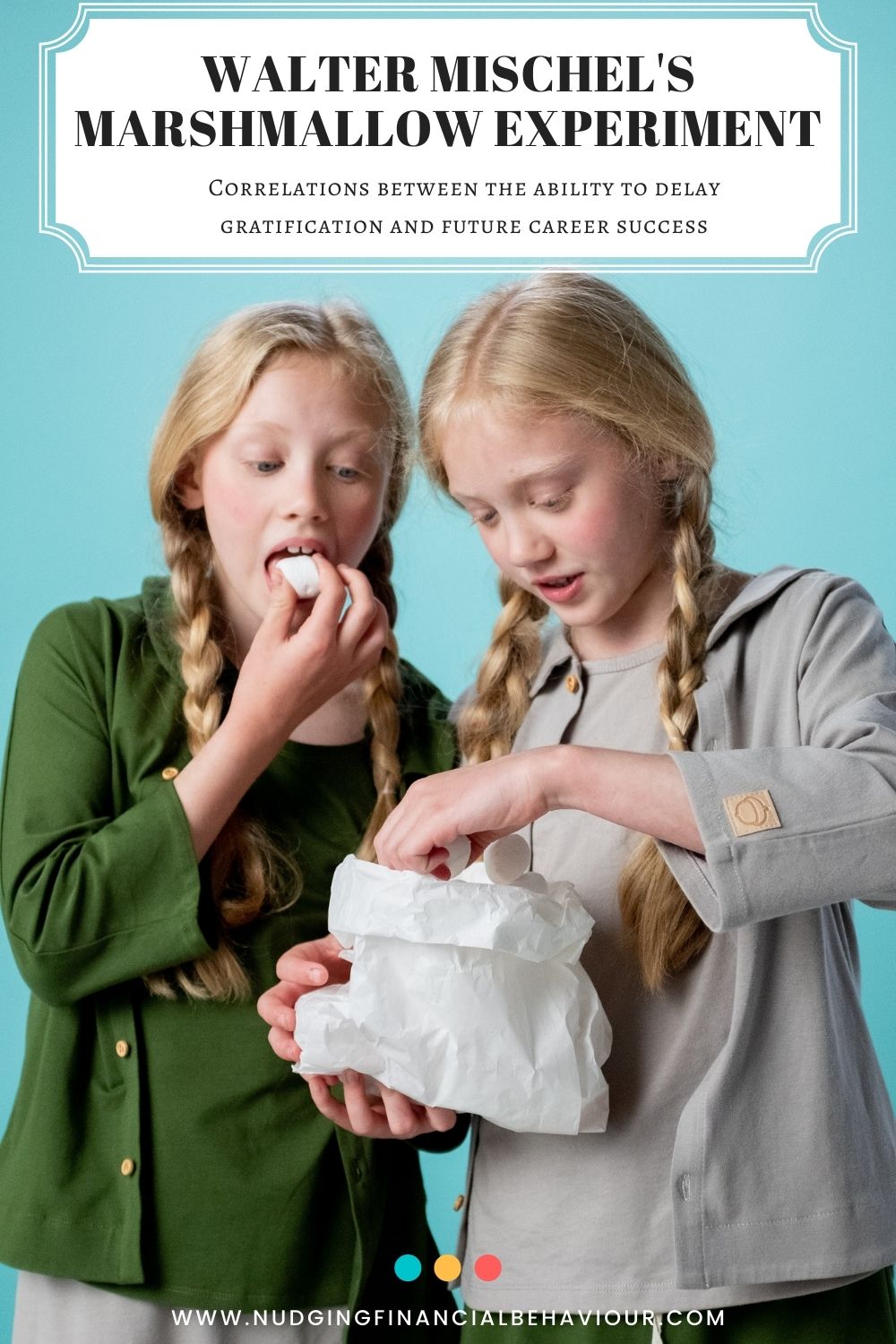

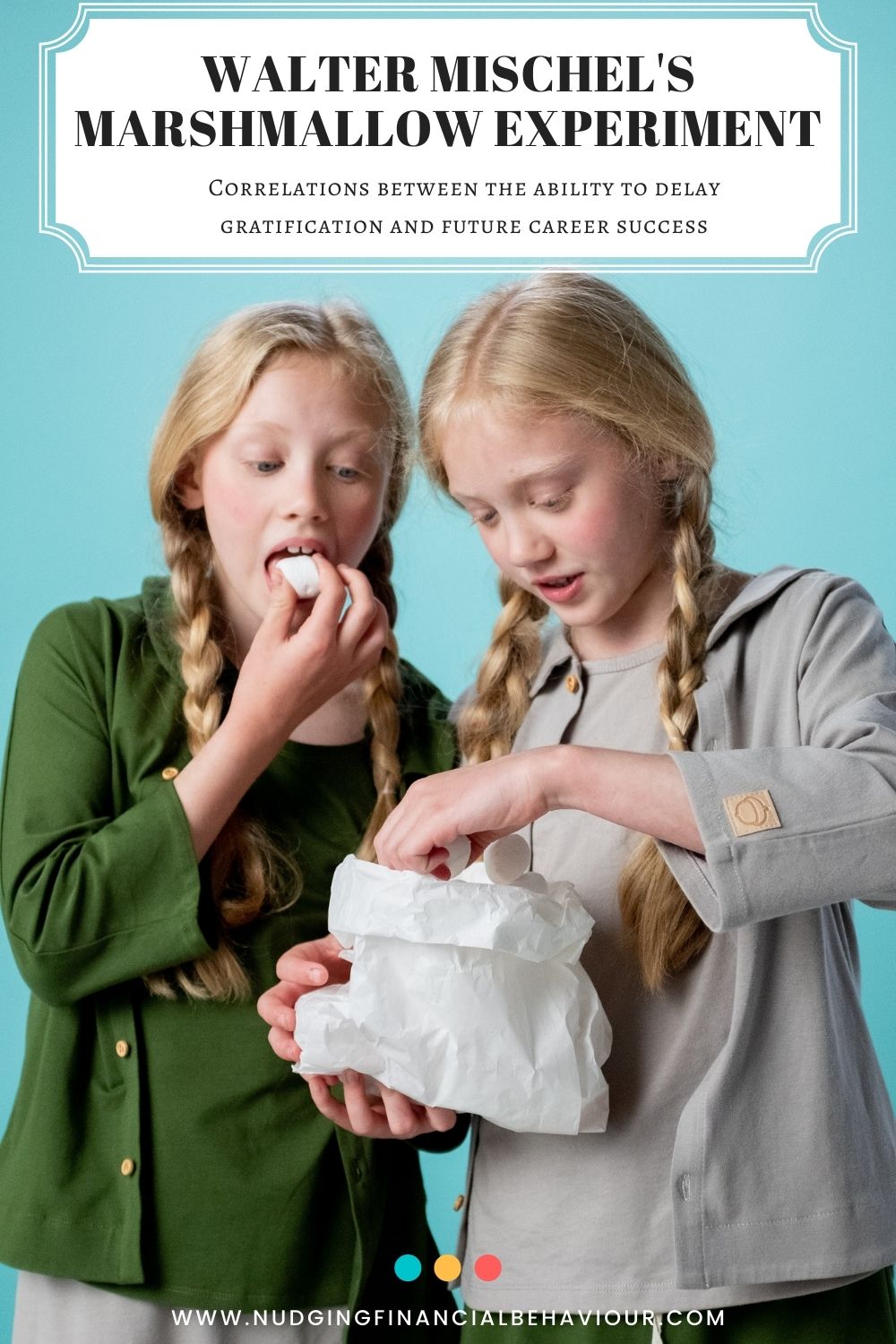

The very well-known marshmallow experiment by Walter Mischel illustrated that this is part of who we are, not just an artefact of economics. In his hyperbolic vs exponential discounting experiment, children (aged 4) were given 1 marshmallow. They were told that if they could wait and not eat that 1 marshmallow, they would be given a 2nd marshmallow. Extreme self-control and willpower was needed from these children to wait and not eat that marshmallow, for the reward of 2 marshmallows. And, as can be expected, many of the children couldn’t wait. The value of this study lay in that it tracked these children over their lives and started to see correlations between their ability to delay gratification (by those children that could wait) and future career success.

The very well-known marshmallow experiment by Walter Mischel illustrated that this is part of who we are, not just an artefact of economics. In his hyperbolic vs exponential discounting experiment, children (aged 4) were given 1 marshmallow. They were told that if they could wait and not eat that 1 marshmallow, they would be given a 2nd marshmallow. Extreme self-control and willpower was needed from these children to wait and not eat that marshmallow, for the reward of 2 marshmallows. And, as can be expected, many of the children couldn’t wait. The value of this study lay in that it tracked these children over their lives and started to see correlations between their ability to delay gratification (by those children that could wait) and future career success.

These findings were backed up by another study that followed 1000 children from birth to the age of 32. It was found that self-control during the first decade of life predicts income, savings behaviour, financial security, physical and mental health, substance use, and (lack of) criminal convictions, among other outcomes, in adulthood. Extraordinarily, the predictive power of self-control can be compared to that of either general intelligence or family socioeconomic status. Perhaps teaching our children to delay gratification is one of the best skills we can teach them? The study only tracked the participants till their early thirties, so who knows how things turned out later in life?

Patience is a virtue Share on XHow often with online shopping don’t you see the same item at two different prices? One is in stock, the other you need to wait a couple of days. It baffles me, as surely the item is in stock till it’s sold out? Then you’ll need to wait a couple of days while they order some more. But no – they’re playing on your need to have it now and charging you more. They’re betting on you to discount future present values hyperbolically.

The biggest issue I have with credit is that it gives us the option of paying LATER for something that we want NOW. We get the benefit of the goods, with none of the pain of payment. This exacerbates our self-control problem. Remember, we’re time-inconsistent and discount hyperbolically, not exponentially.

The obsession with instant gratification blinds us from our long-term potential.

Let’s look at a study that analysed this hyperbolic discounting in the credit card market. Two credit card offers were made: both with low introductory rates. The one offered a very low rate for a short period of time, after which it rose quickly. The second offered a slightly higher rate, still, a reduced one though, which stayed consistent at that rate over the entire period.

The rational discounter would take the second card, as it yields lower interest payments over the full period. But overwhelmingly, participants preferred the first card with the very low introductory rate. Why? Because we don’t foresee that we’ll still have the debt after the initial low-rate period. We truly believe that our future self is going to pay off that debt before the term of the initial low-rate passes. But in reality, we don’t.

Let’s look at a study that analysed this hyperbolic discounting in the credit card market. Two credit card offers were made: both with low introductory rates. The one offered a very low rate for a short period of time, after which it rose quickly. The second offered a slightly higher rate, still, a reduced one though, which stayed consistent at that rate over the entire period.

The rational discounter would take the second card, as it yields lower interest payments over the full period. But overwhelmingly, participants preferred the first card with the very low introductory rate. Why? Because we don’t foresee that we’ll still have the debt after the initial low-rate period. We truly believe that our future self is going to pay off that debt before the term of the initial low-rate passes. But in reality, we don’t.

We give our future selves way more credit than they deserve. And we underestimate the power of compound interest, once again.

Sometimes, I’m not even convinced we think that far ahead. We’re just interested in getting our hands on the latest gadget NOW, no matter the cost.

Investing is not only about hard work (figuring out which company is a good option and at what price), but also about mental discipline. The ability to delay gratification, to sacrifice now for a later benefit, is the hallmark of a good investor.

Day traders or anyone making short-term trades are almost destined to lose money unless they have some sort of information advantage. There are exceptions to this rule (don’t send me hate mail). For most people though, the advantage is being able to wait.

Great investing requires a lot of delayed gratification.

Thus, if you’re the kind of person who can’t wait to upgrade to the latest iPhone and doesn’t hesitate to charge something to your credit card, perhaps you’re better off putting your money in index trackers?

Great investing requires a lot of delayed gratification.

Thus, if you’re the kind of person who can’t wait to upgrade to the latest iPhone and doesn’t hesitate to charge something to your credit card, perhaps you’re better off putting your money in index trackers?

Unlike most behavioural biases, which are seemingly unconscious, self-control is something we can make a concerted effort to improve. For parents, lack of self-control can be detected early in children and interventions improve your children’s opportunities significantly. Go grab some marshmallows and test your four-year-old (let me know how it goes).

Finally, let me categorically say that I’m not anti-credit cards (although I am breaking out into a cold sweat as I type this), I’m just concerned about our lack of self-control when using them. Is it too much to ask that financial service providers ask clients to pass a simple test to calculate, and understand, compound interest before issuing them credit? If they’re that adamant to issue the credit, perhaps provide the requisite training and education?

When you delay instant gratification, you will experience long-term satisfaction. Share on XLet us know in the comments below.

I am passionate about helping people understand their behaviour with money and gently nudging them to spend less and save more. I have several academic journal publications on investor behaviour, financial literacy and personal finance, and perfectly understand the biases that influence how we manage our money. This blog is where I break down those ideas and share my thinking. I’ll try to cover relevant topics that my readers bring to my attention. Please read, share, and comment. That’s how we spread knowledge and help both ourselves and others to become in control of our financial situations.

Dr Gizelle Willows

PhD and NRF-rating in Behavioural Finance

[user_registration_form id=”8641″]

“Essentially, all models are wrong, but some are useful.” – George E.P. Box

Receive gentle nudges from us: